Draycott Bio Shines New Light on a Woman Reviled by Cicero as Conniving and Rapacious

The problem for a biographer, as the author points out, is that the accounts of Marc Antony’s wife Fulvia are almost all negative and written by males.

‘Fulvia: The Woman Who Broke All the Rules in Ancient Rome’

By Jane Draycott

Yale University Press, 296 pages

Fulvia who? Marc Antony was one of her three husbands who benefitted not only from her housewifery but from her tenacious accumulation of land, wealth, and political power while giving birth to his children and incurring the enmity of Rome’s leadership classes — especially Cicero, who never ceased excoriating her as a conniving, greedy, rapacious unwomanly woman who even went to war.

So how is it that Fulvia is not better known? To some extent, it is a matter of timing — as Jane Draycott observes. The women who took charge in the Roman Empire 100 years after Fulvia did not acknowledge her, yet they profited from her formidable example, so that their own power moves were deemed not so aberrant as those in Fulvia’s day.

Fulvia is not so well known because she left behind no written record, no cadre of followers who might have burnished her reputation. In the Rome of her time, she made a public display of herself, which the Roman patriarchy deplored as unbefitting a well-born woman.

Antony’s reliance on Fulvia’s counsel and her strategizing signaled to his enemies a weakness in a soldier who could not resist the wiles of women like Cleopatra. As a result, the supposedly grasping Fulvia was isolated as a malign anomaly.

Was Fulvia as bad as her male enemies contended? The problem for a biographer, as Ms. Draycott announces from the get-go, is that with one notable exception, the accounts of her are all negative and all male. Ms. Draycott is suspicious because the diatribes are full of the invective used against women who asserted themselves.

Ms. Draycott’s mission is not so much to expunge the rap sheet on Fulvia as to suggest that her aggressiveness did not differ from that of her male contemporaries who went about reviling one another and sometimes murdering rivals in a fragile republic headed toward empire. The biographer seeks not to excuse Fulvia but to show the limited options available to the wives of men who were murdered or died in battle.

Fulvia’s power moves, Ms. Draycott notes, protected her and her family against hostile forces. Without lands, titles, or political influence, a wife and mother could not survive, let alone prevail. Three of her children would die violently and Antony would divorce her; yet Fulvia kept coming on, holding her own until Antony lost out to Octavian and she died in exile.

In addition to helpful maps, illustrations, a family tree, a timeline, and a note on Roman names, Ms. Draycott includes an indispensable appendix: “Ancient Sources for Fulvia,” assessing the important accounts and suggesting their authors’ varying motives and reliability.

In a conclusion assessing Fulvia’s legacy, Ms. Draycott shows her subject’s appearance in modern sources, including television and movies, to have been minimal. Rarely is she given credit for shoring up the ungrateful Antony in his efforts against Octavian.

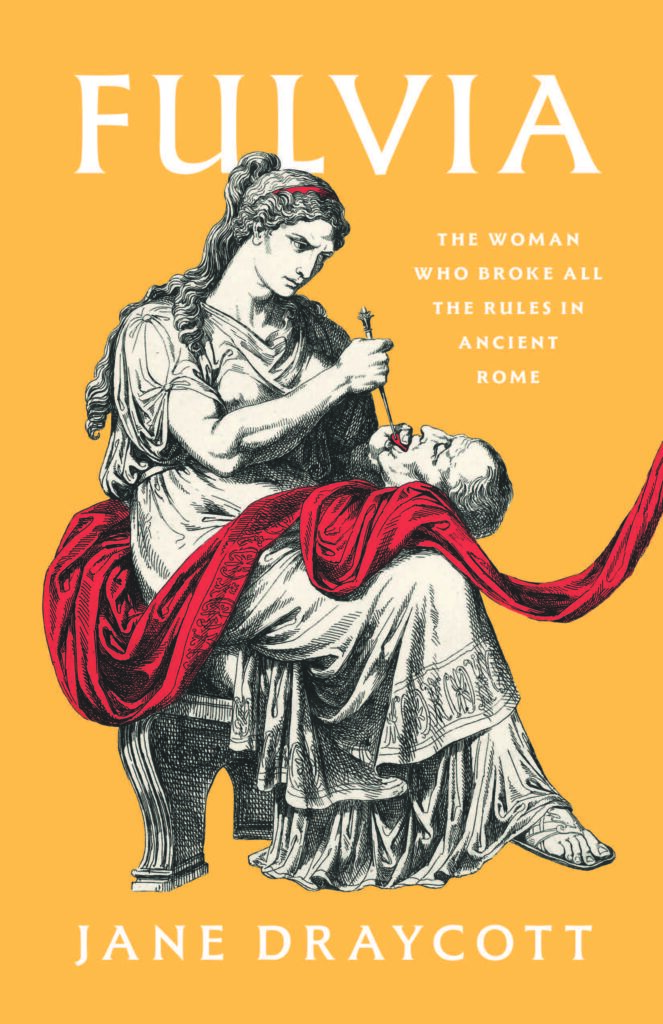

Yet, look at the cover of Ms. Draycott’s biography: There is Fulvia with the severed head of Cicero in her lap. Ms. Draycott calls the gruesome scene “one of the most infamous episodes in Fulvia’s life and career. … When Cicero’s head was presented to her, she reportedly spat on it, then retrieved a hairpin from her elaborate coiffure and proceeded to stab his tongue.”

Many artists have depicted a bloodthirsty Fulvia, and Ms. Draycott describes their versions, noting as well that the “vignette of an unforgiving woman arming herself with a hairpin and using it to wreak vengeance” occurs in Apuleius’s novel “Metamorphoses.”

The implication is that the depiction of Fulvia with Cicero’s head may be fictional as well. Or, if not, “might she have been treating it more in the manner of a Kolossos, or voodoo doll, and attempting to bind it so it could no longer slander her and her nearest and dearest?” Cicero had cursed her, Mrs. Draycott reports, and so Fulvia cursed him back.

At any rate, Ms. Draycott argues, Fulvia participated in a revenge culture, amplified on Roman curse tablets. Might the cover, then, of Ms. Draycott’s book announce her own effort to lift the curse on her subject?

Mr. Rollyson is the author of the forthcoming “Sappho’s Fire: Kindling the Modern World.”