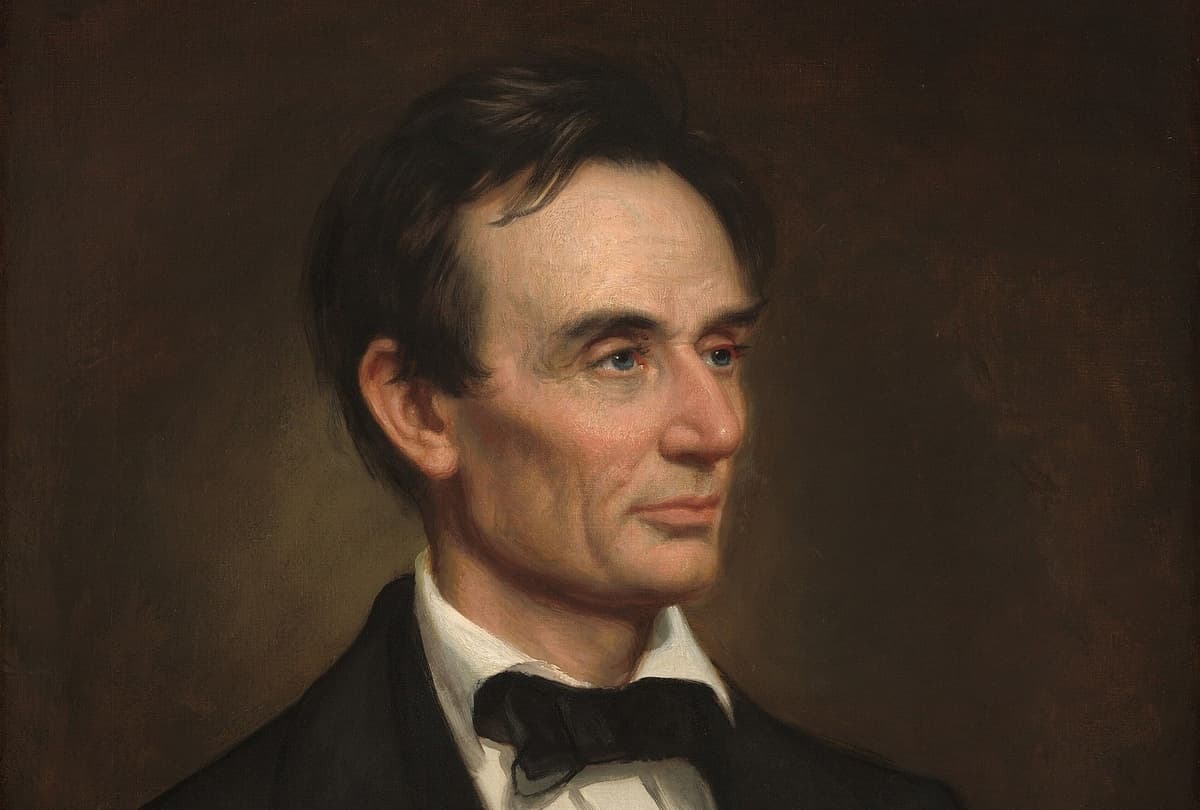

How Lincoln Restored Himself to Greatness

Saladin Ambar contends that Lincoln early on understood that the obsession with race was a key way of understanding the undermining of American institutions.

‘Murder on the Mississippi: The Shocking Crimes That Shaped Abraham Lincoln’

By Saladin Ambar

Diversion Books, 240 Pages

The most arresting sentence in ‘Murder on the Mississippi,” one that takes issue with generations of Lincoln biographers, is predicated on a risky but plausible premise: “Abraham Lincoln did not grow into greatness. He reclaimed it.”

Saladin Ambar builds his biography around a single speech, included in an appendix: “On the Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions. Address Before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois,” January 27, 1838. He argues that a profound backstory about race is buried in such a way as to have eluded the notice of even Lincoln’s most profound biographers.

Mr. Ambar contends that Lincoln early on understood that the obsession with race was a key way of understanding the undermining of American institutions by the resort to mob rule that threatened whites and blacks alike, and would result in the suicide of a nation that no longer understood or honored the first principles of its Founders.

Here is the passage that excited Mr. Ambar’s interest, detailing the “horrors,” as Lincoln called them, “revolting to humanity”:

“In the Mississippi case, they first commenced by hanging the regular gamblers; a set of men, certainly not following for a livelihood, a very useful, or very honest occupation; but one which, so far from being forbidden by the laws, was actually licensed by an act of the Legislature, passed but a single year before. Next, negroes, suspected of conspiring to raise an insurrection, were caught up and hanged in all parts of the State; then, white men, supposed to be leagued with the negroes; and finally, strangers, from neighboring States, going thither on business, were, in many instances subjected to the same fate. Thus went on this process of hanging, from gamblers to negroes, from negroes to white citizens, and from these to strangers; till, dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every road side; and in numbers almost sufficient, to rival the native Spanish moss of the country, as a drapery of the forest.”

Lincoln reached what he considered the inevitable conclusion: As soon as respect for the rule of law is abrogated, no citizen is safe. Lincoln sought to show that race was not a separate issue, a set aside, that could be dealt with later. What was done to slaves and free black men could be done to anyone.

Mr. Ambar demonstrates that Lincoln’s anti-slavery stance in the 1830s had no political benefit and might even have harmed his prospects for high office. No other politician in Illinois was so forthright about the evils of slavery. In fact, Lincoln had no allies in the Illinois state legislature, and it could not be said that public opinion was on his side.

Lincoln deplored mobocracy personified by the president he opposed: Andrew Jackson, who cared more for the popular sovereignty of the people than for the rule of law. By the 1830s, Americans of the founding generation were no longer available to perpetuate its founding convictions, leading to, Lincoln feared, the weakening of democratic institutions.

In his Lyceum speech, Lincoln declared that if America was to fail it would be because of an internal threat. No power beyond the geographical boundaries of the country would ever be as dangerous as what the country harbored within itself. Later, as Lincoln became more prominent, he temporized, Mr. Ambar acknowledges, emphasizing that keeping the Union together was more important than the extirpation of slavery.

In the end, however, as the Union came apart, Lincoln returned to his own radical view of how race, mobocracy, and the rule of law were entwined.

In a final chapter, Mr. Ambar relates Lincoln’s grave concerns about mobocracy with the events of January 6, 2021, quoting Congressman Jamie Raskin, who had invited his daughter and son-in-law to the Capitol: “And then there was a sound I will never forget: the sound of pounding on the door like a battering ram. It’s the most haunting sound I ever heard, and I will never forget it. My chief of staff, Julie Tagen, was with Tabitha and Hank, locked and barricaded in that office, the kids hiding under the desk, placing what they thought were their final texts and whispered phone calls to say their goodbyes. They thought they were going to die.”

Mr. Rollyson’s forthcoming book is “Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History.”