In ‘100 Objects,’ YIVO Traces Jewish Diaspora Experience of Building Community From What Was at Hand

The items, compiled in a new book marking the institute’s centenary, are intimate, deeply interesting, occasionally appalling, and more than a little melancholy.

‘100 Objects from the Collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research’

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

Hardcover, 332 pages

Diaspora is the unifying experience of the Jewish people. Cobbling life together during fits and starts of settlement, exile, and persecution, Jews have always had to build communities out of whatever was at hand. New York’s Institute for Jewish Research, known as YIVO, is a historical research body dedicated to collecting these cultural objects and remnants. Now, 100 of these artifacts, selected from their vast archive, have found their way into a book.

“100 Objects,” published in honor of YIVO’s 100th anniversary, is a handsome coffee table tome that gathers these remnants onto its pages. Beautifully photographed and accompanied by meticulously researched scholarly text, it creates a powerful archival testament to the adaptive and enduring spirit of Eastern Europe’s Jews. As stated in YIVO’s founding appeal, the organization is enjoined to “Gather…these remnants that have been left to us as a cultural inheritance.”

To leaf through these pages is much like rummaging through the effects of a departed relative. The objects are intimate, deeply interesting, occasionally appalling, and more than a little melancholy. Taken as a whole they encompass the richness of Eastern European Jewish life, even in exile. From sketches of Marc Chagall to hats from the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, an astonishingly broad range of artifacts are here.

There are sacred texts, such as the Rothschild Talmud, alongside folk superstitions scrawled in Yiddish. There is a deed for a Jewish children’s orphanage, and Chaim Grade’s Hebrew Typewriter. Toys, household objects, Judaica, clothing, shoes and other cherished keepsakes show us Jewish life of the last 100 years from every conceivable angle.

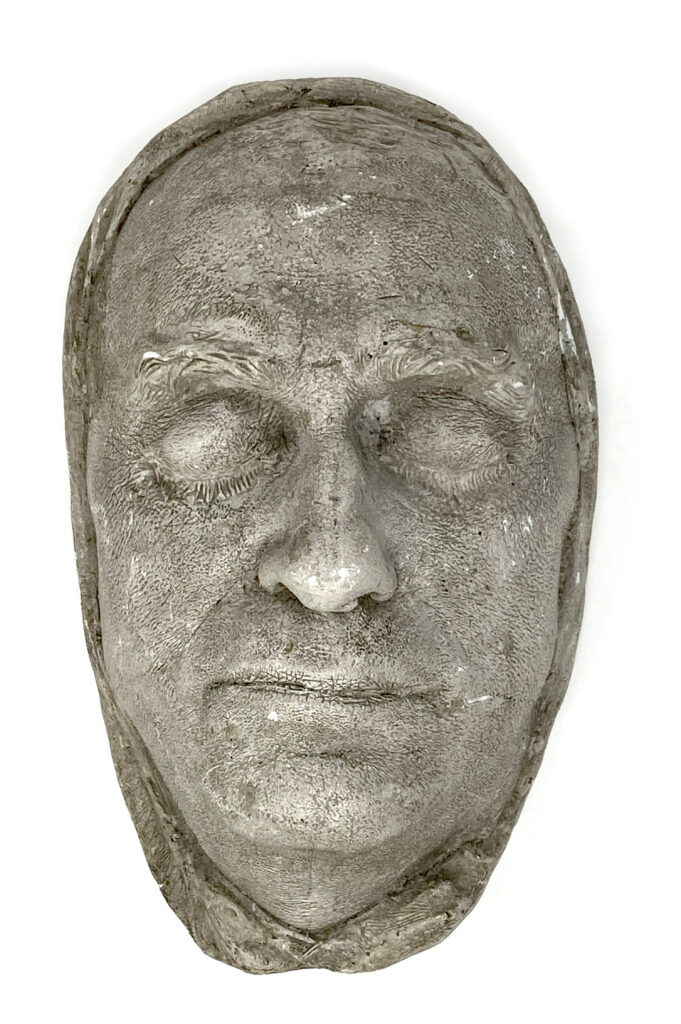

This includes the tremendous cultural legacy of Jews in arts, letters and entertainment. The plaster death mask is here of the poet and raconteur Yehoash, or Solomon Blumgarten, whose Yiddish translation of the Hebrew Bible graced nearly every Jewish household the world over. A star of the Yiddish stage and screen at the height of the roaring twenties, Mae Simon, is represented by her snazzy red satin shoes. A 1936 cinema poster for Yiddish cinema, a musical comedy entitled “Yidl Mitn Fidl,” attests to Yiddish culture’s international appeal just before World War II.

Legal documents and records open a rare window into the workings of Jewish daily life. There is a police file searching for a derelict Jewish husband on the lam from his family. An 1874 petition to a rabbi from a Polish tavern owner expresses the fear he may be unfairly deprived of his business. A census register of Sephardic Jews from Salonica, Greece, displays an ominous demographic shift in its signed pages. It forms a chilling book end to another notebook, the “arrivals and departures” ledger for Auschwitz Block 8. Archives often speak louder and more eloquently than testimony.

Snapshots of political life abound as well. The inclusion of Birobizhaner Schtern, a Soviet wall newspaper, along with a copy of the Jewish Daily Baker, a working people’s paper from the thirties, attest to the complex political history of Jews abroad. It is marked by their strong embrace of proletarian and labor-centered causes, just as Jews would strongly champion Civil Rights in the 1960s. There is also a copy of America’s Declaration of Independence translated entirely into Yiddish, and the early personal diary of the father of modern Zionism, Theodor Herzel.

Pointed artifacts of antisemitism further underscore how the world’s oldest hatred has always been at a simmer when it isn’t boiling over. A letter from Lake Mohonk Mountain House at New York’s Ulster County, dated 1922, crisply informs a Jewish job applicant that “we do not employ people of your race.” A chillingly bland portrait of Nazi official Arthur Seys-Inquart, painted directly onto a cut piece of Torah Scroll, reminds us that desecration of sacred Jewish artifacts was a cherished hobby of the National Socialist Party.

Finally, the stark realities of the Shoah are brought home, often in unexpected ways. Colorful dolls, manufactured at a displaced persons camp at Florence, highlight the displacement experienced by survivors of the Holocaust. They evoke the painful and often absurd predicament of Jews who had nowhere to go.

Collectively the objects yield an overarching truth. They bear witness to a life replete with religious observance, literature, theatre, dance, visual art, cinema and a rich political tradition of advocacy and activism. It also points to antisemitism, displacement, pogrom, and ultimately Shoah.

There is another unifying thread: a continuous signaling towards Israel as an ultimate destination. From the turn of the 19th century onwards, Israel is the goal for a scattered populace struggling to find a place where they can finally be a settled and self-determined people. At this particular historical juncture, where old untruths and distortions are making an unwarranted and astonishing comeback, YIVO’s work is more pressing than ever.