Josiah Wedgwood and the Melancholy of Mechanized Perfection

In effect, the author suggests Wedgwood’s unremitting effort to reconstitute the classical world in ceramic form parallels — if it was not caused by — the loss of his own limb.

‘Melancholy Wedgwood’

By Iris Moon

The MIT Press, 248 Pages

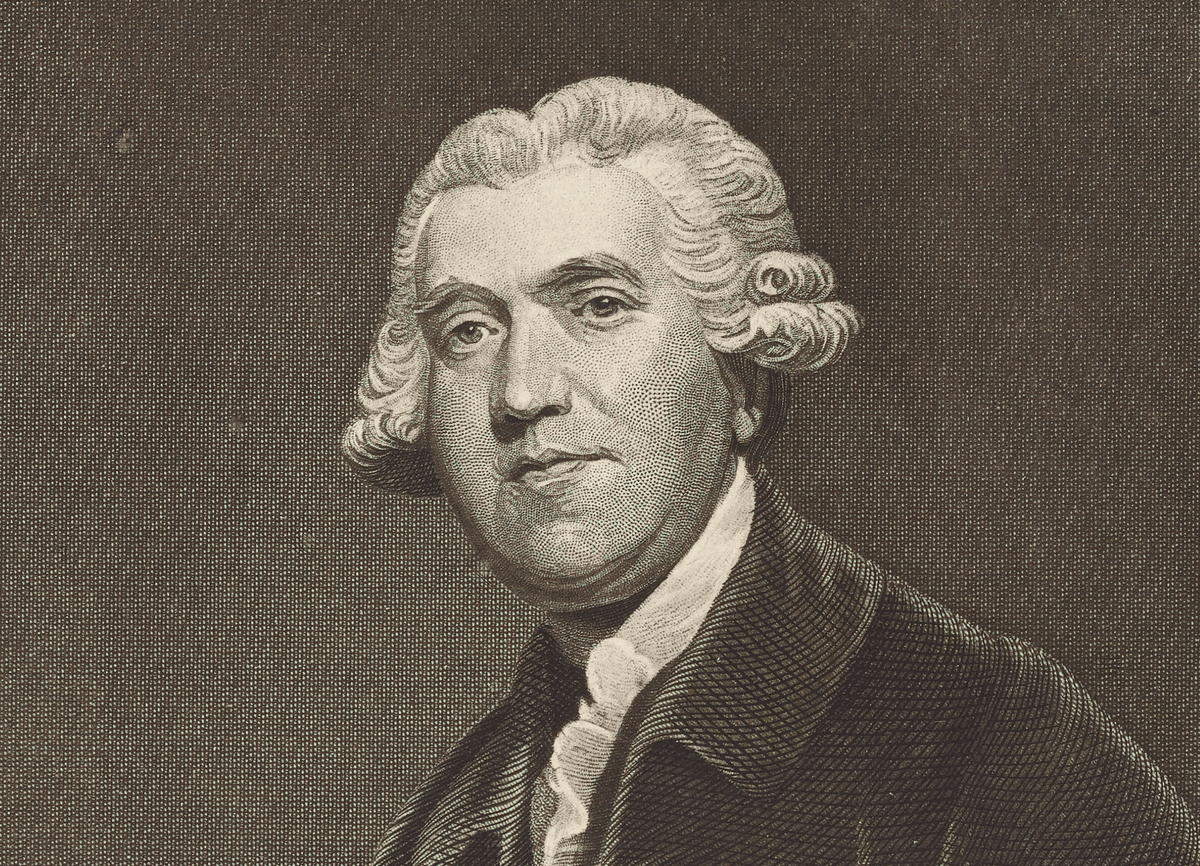

Josiah Wedgwood, who was born in 1730 and died in 1795 and was famous for his ceramics, created a neoclassical body of work for a commodity culture desiring new pottery and stoneware that had the look of antiquity even as England’s industrial output accelerated and the very meaning of labor was transformed in the factory of entrepreneurial innovation.

Iris Moon calls her book an “experimental biography.” She eschews a chronological approach that, in her view, enhances the mythology of progress through an industrial revolution that in its wake left piles and piles of wasted materials and lives in the dynamic of capitalists like Wedgwood who were determined to invent — at whatever cost to themselves, their families, and their employees — useful and often beautiful objects that glorified households and signaled the rise of modern business as synonymous with the rise of an empire.

Ms. Moon fastens on a biographical fact, noted in every biography of Wedgwood without much comment: After he lost a leg, he could no longer seat himself at a pottery wheel. In grievous pain, he had welcomed the amputation, recovering well and then rarely mentioning his disability — one that was never, in his own country, shown in images of him.

If Wedgwood ever spent much time as a melancholic, no biographer has ever established as much. Yet that does not deter Ms. Moon, noting how much melancholy has in fact been part of the fabric of English life, dating back at least to Robert Burton’s “Anatomy of Melancholy” from1621.

To understand how Burton inspired Ms. Moon to give Wedgwood a new look and a decidedly contrarian treatment compared with previous accounts of his life and work, the full title of Burton’s masterpiece has to be given: “What it is: With all the kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Main Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up.”

What Burton does for melancholy, Ms. Moon does for Wedgwood, suggesting that losing a limb exposed him to a sectioned, dismembered, and fragmented world that he reunited in the many vases and urns and other vessels that were the result of numerous failed experiments in the intense fires of his factory, the rubble of which Ms. Moon could still find on a recent visit to England.

In effect, she suggests Wedgwood’s unremitting effort to reconstitute the classical world in ceramic form parallels — if it was not caused by — the loss of his own limb. Making bodily figures out of ceramics was a way of reconstituting himself, inventing industrial processes that no matter the perpetual failures resulted in the discovery of that pale blue jasperware coveted to this day for a purity of color like no other to be found except in the firmament.

Reading Ms. Moon on what a Wedgwood work signifies — often not what was intended to begin with — is to plunge deeply into a Burton-like philosophical, historical, and medical operation that cuts and opens up a primal response to melancholy that has been covered with the patina of pottery that is still very much prized today.

Wedgwood, a man of tremendous energy, never seems to have paused for a moment to inquire into the origins of his manic activity. Ms. Moon does that for him, slowing down the manufacturing process, turning her Wedgwood over and over again, finding new meanings in old objects, or new objects made to look old.

Biographers often deal with their subjects’ children as a way of considering what has been left by way of a legacy to posterity. In this unfortunate instance, none of Wedgwood’s children took much interest in their inheritance or were able to sustain the business of the founder.

An especially melancholy case is Wedgwood’s son, Tom, sickly from the start and never able to recover his health, succumbing to the sad outcome that his father staved off by his incessant labors. Tom had the leisure to contemplate his maladies and the intelligence to almost invent photography before Henry Fox Talbot, but was unable to quite bring his experiments to the point of scientific proof. As such, his story provides a curious coda to a Wedgwood generation with too much time on its hands.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “A Higher Form of Cannibalism? Adventures in the Art and Politics of Biography.”