Luxurious and Surrounded by Armed Guards, Zohran Mamdani’s Family Rental Is Steeped in Inequality

Just beyond the fences, the Ugandan streets teem with boda-boda drivers, market women, and day laborers — but you’d never know it inside the compound.

The cobblestone path winds upward through a garden that feels less like a front yard than a tangle of exquisite jungle — wild, deliberate, and expensive to maintain. Chickens dart through the undergrowth and tropical birds chatter above the palm trees like noisy ornaments.

By the time I reach the tall iron gates, sweat is already rolling down my back in the Ugandan sun. Two armed soldiers step forward, unsmiling, rifles slung casually across their shoulders — the casualness itself a kind of menace. They’re not police. They’re the real thing, the kind of protection usually reserved for politicians and generals.

This isn’t the State House or a foreign embassy. It’s an Airbnb.

Specifically, the Mamdani family’s Airbnb: five bedrooms, four baths, set on a hill above Lake Victoria. It’s a 20-minute drive from the bustle of downtown Kampala, but a world away in every other sense.

“They don’t allow filming or photos,” a caretaker explains, referring to the owners. “If you’re a guest, you’re there to stay, not to take videos.”

Inside, the gates swing open with a metallic groan and I step into an oasis — manicured gardens tumbling toward a private lap pool and badminton and tennis courts. Labradors sprawl lazily in the shade, and vines curl over stone walls that look as if they’ve stood here forever.

The neighbors? Uganda’s vice president, Jessica Alupo; President Yoweri Museveni’s son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, who happens to be in charge of Uganda’s defense forces; and a roster of army brass. The neighborhood itself whispers of old money and new power — tree-lined avenues where every compound hides behind bougainvillea, high fences, and the low, steady hum of diesel generators.

Just beyond those fences, Kampala’s streets teem with boda-boda drivers, market women, and day laborers hustling for a few dollars. But here, you would never know it.

The Airbnb listing reads like an architectural fantasy: Roberto Burle Marx and Geoffrey Bawa inspirations, an “artist’s garden” spilling with tropical color, “non-aggressive monkeys at dawn.” It is all true — and then some.

I wander through verandas furnished with carved wooden chairs, English-style portraits, Hindu symbols — subtle nods to the family’s heritage — and hundreds of aging books stacked in a library alcove. Every surface whispers of old wealth, the kind of wealth that doesn’t just decorate, it employs.

Indeed, they are all here: gardeners who prune the jungle into art, and a cook who serves up eggs and sausages for breakfast, then chicken and chips for lunch, with strong coffee in between.

Life here is unhurried — guests don’t cook, don’t clean, don’t even pour their own coffee unless they insist. Outside the gates, men push wheelbarrows of bricks in the sun and women balance jerrycans on their heads; inside, labor is quiet, uniformed, and underpaid.

The home itself isn’t flashy in the way American luxury homes can be. There are no stainless-steel appliances, no wall-sized televisions. Instead, its wealth discloses itself in subtler, sturdier ways: thick timber beams, polished floors, hand-carved shutters that swing open to catch Lake Victoria’s breeze.

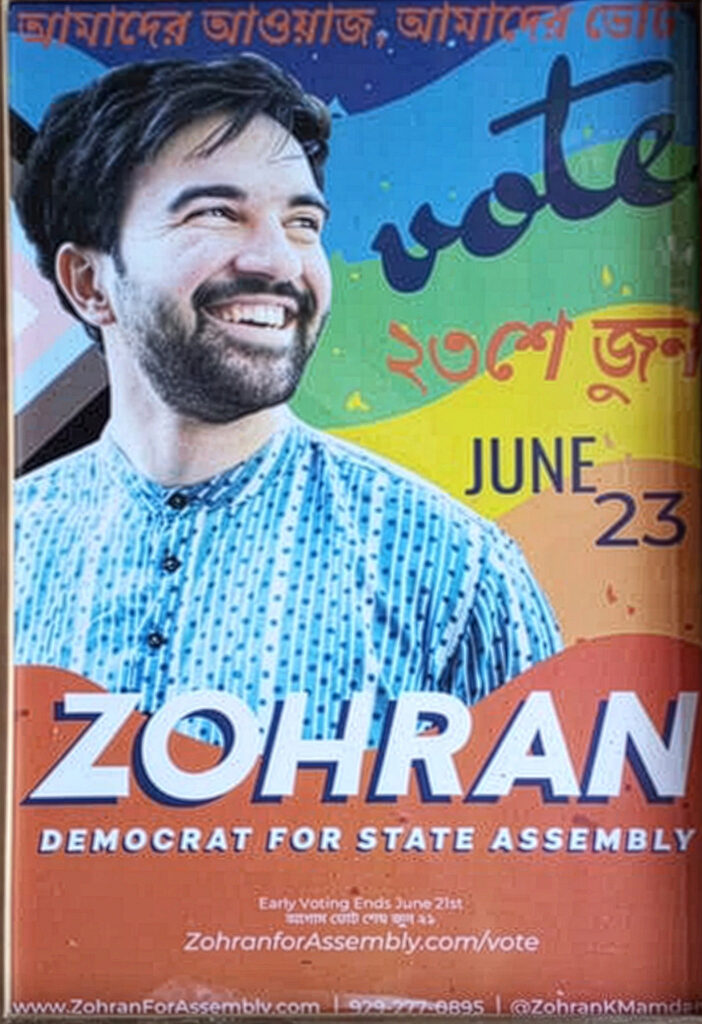

On the walls hang old photographs, family relics, and English prints — less curated gallery than accumulation of decades of privilege. Most notably, a “Democrat for State Assembly” poster of a smiling Zohran in traditional dress cast against bright rainbow colors anchors the living room wall like an inside joke.

The spacious five-bedroom, four-bathroom home feels lived-in and layered, not a showpiece for strangers but a true family compound — the kind that doesn’t just house comfort but reproduces it for generations.

It is, in a word, privilege.

It belongs to the family of Zohran Mamdani, the far-left New York assembly member turned Democratic Socialist nominee for mayor. The same Mamdani who campaigns on dismantling systemic inequality, railing against landlords, wealth, and privilege.

Yet here I am, living like a Mamdani, in one of the most exclusive enclaves of Uganda, surrounded by armed soldiers, servants, and lake views that most Ugandans could never dream of affording.

The contradictions are hard to ignore. Zohran Mamdani often tells the story of his early Ugandan childhood, of being forced to leave when his family emigrated, of returning briefly at 21 when his father took a sabbatical. It may not be the whole story.

His father, Mahmood Mamdani, is one of Africa’s most prominent intellectuals, a scholar revered across Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda. His mother, Mira Nair, is a celebrated filmmaker. In fact, the 1991 Denzel Washington film “Mississippi Masala” was filmed here, directed by Ms. Nair.

Their friends include presidents and vice presidents, their circle populated by elites. The family’s home reflects it.

The staff know their place; the soldiers know theirs. Guests are expected to enjoy the grounds, not document them. Privacy is prized, even as the property itself is offered for rent to strangers with the right bank card. It is the paradox of elite life in Kampala: both guarded and for sale, both private and performative.

Standing by the pool, I look out over Lake Victoria as the sun dips low. It is so incredibly quiet and serene, I have to remind myself of where I am. The water glitters gold, the air is soft, the only sounds are the birds in the garden and the distant thwack of a tennis ball from the private court below.

It is a scene of peacefulness, luxury, and undeniable beauty — but also one that sharpens the edge of contradiction.

At dawn, monkeys swing lazily in the trees, unbothered by human intrusion. At dusk, the garden lights glow and the soldiers take their positions at the gates. Even the air feels different here, cooler, filtered by the thick canopy of trees.

It is also revealing. For a man who denounces capitalism and campaigns against inherited advantage, the Mamdani life is a world built on both. The family’s wealth, influence, and insulation are not aberrations; they are foundations. To live like a Mamdani, even for a weekend, is to step into a bubble of comfort and security that few in Kampala — or Queens, for that matter — will ever know.

That is the point. Living like a Mamdani is to live behind gates, tended by others, guarded through the night. It is to inhabit a universe where inequality is not an abstraction but the very condition of comfort, where one can rage against privilege in New York while luxuriating in it in Uganda.

I close the shutters as daylight falls and the soldiers take up their posts by the gates. The garden hums with crickets, and the pool reflects the moon. For a brief moment, I imagine what it must be like to grow up in such a place; to know that no matter where in the world you go, there will always be a gate, a guard, and a garden waiting.

Living like a Mamdani is living with a safety net most of us can’t even fathom, including those who surround them.

“I am scared,” one worker says. “I can’t say anything.”