‘Mr. Smith Goes To Washington’ May Get a New Storyline

Democrats, like past parties in disarray, could yet turn to an outsider — in this case one Stephen A. Smith of ESPN.

ESPN’s highest-paid host, Stephen A. Smith, said he’ll “leave the door open” for a Democratic presidential run. He reasons that he has “no choice,” echoing past candidates without political experience who’ve headed tickets for parties in turmoil.

On Sunday, the host of ABC’s “This Week,” Jonathan Karl, asked Mr. Smith if he was “really thinking about running for president.” The sports commentator’s response harkened back to the days when Americans felt that the office should chase the man and campaigning for it was unseemly.

“Listen,” Mr. Smith said, “I have no choice” after “elected officials,” “pundits,” “billionaires and others” approached him “about exploratory committees.” He has “never had a desire to be” a politician, “just signed a contract extension with ESPN” and “couldn’t be happier.”

However, Mr. Smith said that people, including his pastor, have told him, “You don’t know what God has planned for you. At least show the respect to the people who believe in you, who respect you, who believe that you can make a difference in this country.”

With Democrats at record-low favorability in last month’s NBC and CNN polls — 27 and 29 percent respectively — the climate mirrors what Republicans confronted in 2016. They’d lost to President Obama twice and faced a strong candidate in Senator Clinton. Mr. Trump, a long-time Democrat, seemed a sure loser.

Instead, Mr. Trump became the first candidate to win the White House without serving in government or the military. The modern trend for crowded primary fields helped propel him to victory as it could the media-savvy Mr. Smith.

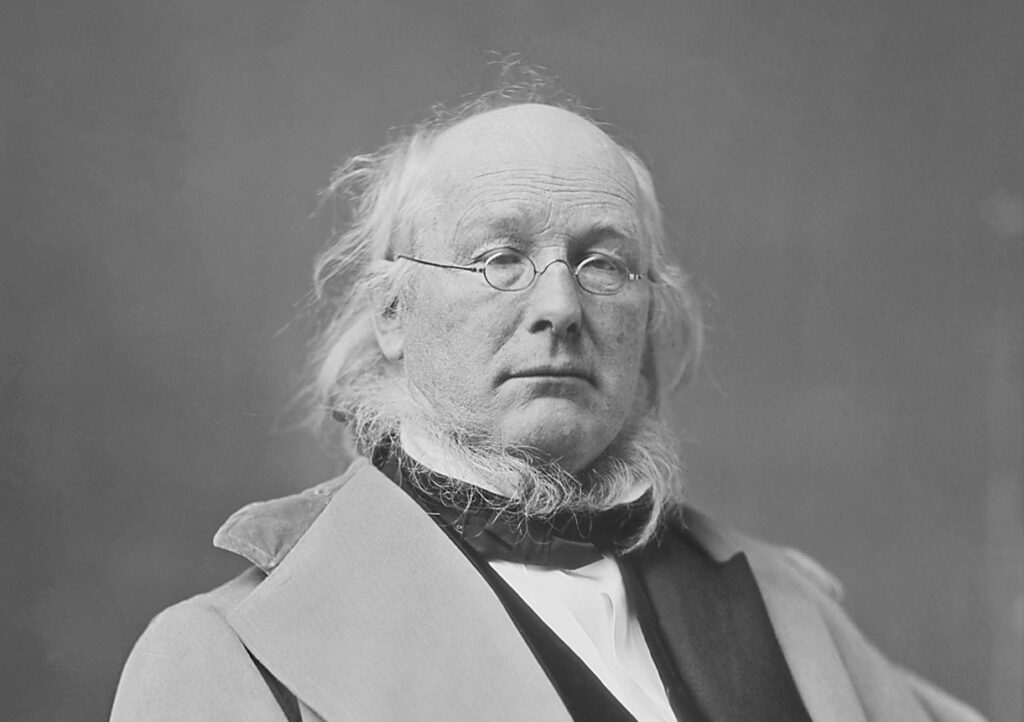

In 1872, another man of the press like Mr. Smith, the scoundrel Horace Greeley, shot for the presidency. The editor of The New York Sun’s bitter rival, the New York Tribune, challenged President Grant, a Republican, who was battling scandals while “waving the bloody shirt” of leading the Union to victory in the Civil War.

Unlike Mr. Trump, Greeley had some political experience in office. He’d served 90 days as a congressman thanks to a special election in 1848 but wasn’t renominated because he’d caused too much trouble by calling out colleagues for missing votes and profiting off their offices.

Greeley wrote the Edgar Allan Poe biographer, Rufus Griswold, that Congress had little desire to make its “crooked paths straight.” After 90 days, he’d “divided the House into two parties,” one that wanted him “extinguished and the other that wouldn’t be satisfied without a hand in doing it.”

On May 6, 1872, the Sun was full of sarcasm for Greeley as the Liberal Republican Party’s nominee. “Grant’s defeat,” it wrote, “is now not only possible, but certain,” if Democrats were “wise enough” to choose him, too.

In a biography of the Sun’s editor, Charles A. Dana, “The Sun Shines for All,” Janet E. Steele writes that Dana, “was convinced that no Democrat stood a chance against Grant in 1872. … He could think of no better sacrificial lamb than Horace Greeley.”

Dana, a former Grant supporter, started boosting Greeley “merely as a joke,” according to his friend, Amos J. Cummings. It was, Ms. Steele writes, “an odd sort of support,” given the feud between the two editors.

The Herald, Ms. Steele writes, lobbied The Sun “not to promote” Greeley “for an office he did not seek.” Dana’s paper “cheerily … chided Greeley for his unwillingness” to serve if called. Unlike Greeley, Mr. Smith is willing to consider a run despite his reluctance.

Democrats — “tainted,” Steele wrote, “with still-lingering charges of disloyalty” — nominated Greeley as their best chance of winning the White House. Grant went on to trounce the Tribune’s man by almost 12 percentage points and shut him out in the Electoral College.

In 1940, with America not yet involved in World War II, it was Republicans slouching through the wilderness. They, too, turned to a member of the opposition: Wendell Willkie. A businessman and World War I veteran, Willkie had been a Democratic activist for years, switching to the GOP late in 1939.

When the Republican Convention deadlocked the following year, he was chosen as a compromise who was above the party’s split over isolationism. The ink was not yet dry on Willkie’s party registration, and he supported some of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. It was, though, enough that he opposed Roosevelt’s expansion of government into areas that Republicans felt the private sector could handle better.

FDR crushed Willkie by ten points in the popular vote, and by 449 to 82 in the Electoral College. Choosing an outsider, it turns out, isn’t a guaranteed cure for an opposition party’s malaise.

In Frank Capra’s masterpiece of a movie, the Mr. Smith who went to Washington as a senator was Jefferson Smith, played by Jimmy Stewart as the leader of a youth movement. Should Democrats fail to find their footing, conditions could well be favorable for an outsider to win their party’s nomination in 2028 — one like Mr. Smith of ESPN.