New Yorkers Hoping To Beat Mamdani Could Learn a Thing or Two From Henry Clay

Is there anyone running in the current contest who would rather be right than be mayor?

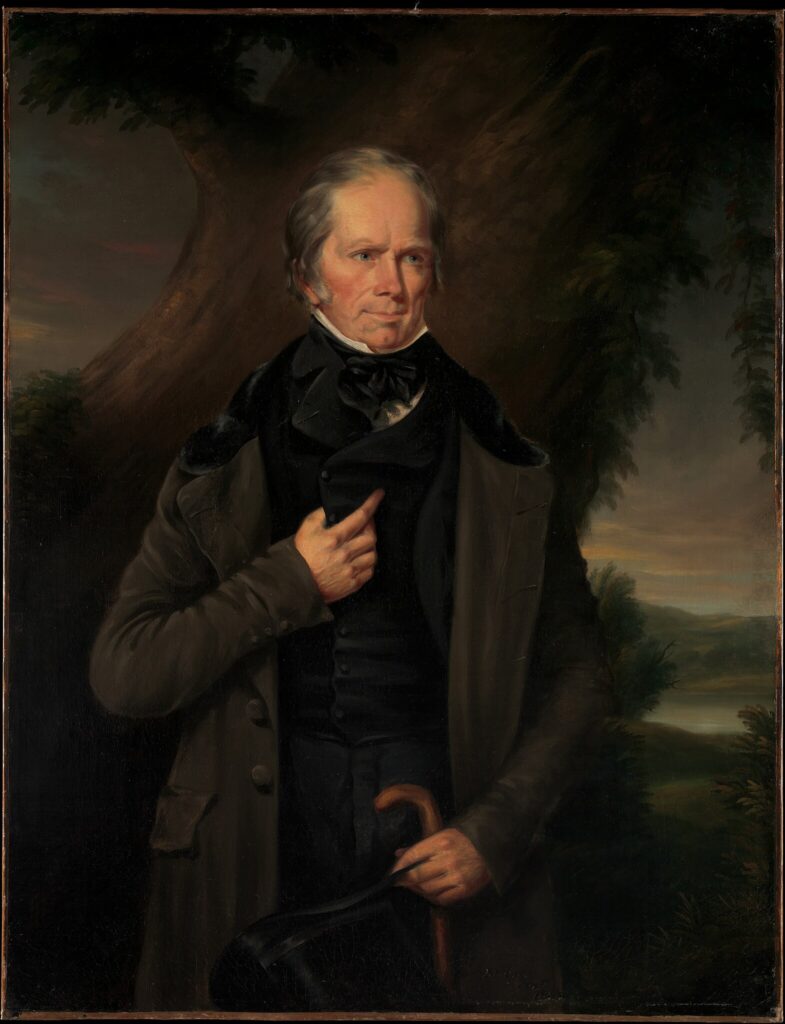

Candidates in Gotham’s mayoral race are calling on each other to drop out to stop the Democratic nominee, Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani. All call the socialist a threat, raising hopes that one or more will show the selflessness of the 19th-century House speaker, Henry Clay, who said, “I’d rather be right than be president.”

Monday morning on CNBC, Mayor Adams recalled Governor Cuomo asking him to leave the race. Mr. Adams said the request displayed “arrogance,” and pointed out that Mr. Cuomo had “just lost” to Mr. Mamdani by 12 points in the Democratic primary.

A top advisor to Mr. Cuomo, Rich Azzopardi, pushed back, contending that Mr. Adams “did not run in the Democratic primary because he knew he was anathema to Democrats and unelectable. Nothing has changed.”

Mr. Adams, at a news conference on Monday, said he thought both Mr. Cuomo and the Republican nominee, Curtis Sliwa, “should rally behind” him. No candidate seems inclined to cede the field, which could split the vote and elect Mr. Mamdani.

“They have come up with all kinds of ways to get me out of the race,” Mr. Sliwa told Bloomberg on Wednesday. He’ll only leave “if something unfortunate happened to me, like me being hit by a Mack truck.”

Mr. Cuomo and a former federal prosecutor, Jim Walden, ignored the June 27 deadline to remove their names from the independent line on the ballot. Mr. Walden is the only one hinting at a willingness to step aside, proposing a survey in September to choose a single candidate to challenge Mr. Mamdani.

In the 1824 presidential election, Clay faced a similar choice between ambition and duty. It was a White House race known as the Battle of the Giants, because all four candidates were heavyweights and two went on to become president.

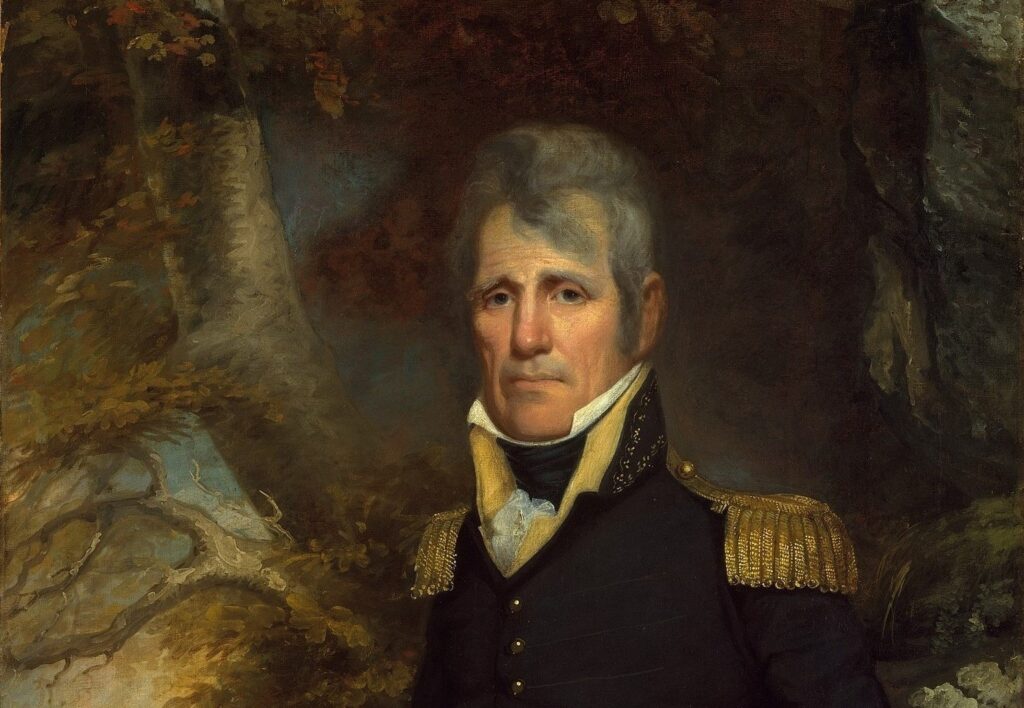

President Jackson won the most popular votes, but not an Electoral College majority. Under the 12th Amendment, the House of Representatives chose between the top three contenders: Jackson, President John Quincy Adams, and Senator Crawford.

Clay, then speaker, failed to place. The Kentuckian detested Jackson, seeing the former general as a threat to the country. The Whigs would later ridicule Old Hickory as “King Andrew the First,” a proponent of direct democracy who’d undermine the Constitution.

Crawford had suffered a stroke, sinking his chances. To stop Jackson, Clay threw his support to Adams, knowing it would cause a backlash. To this day, it’s alleged that the two men hatched a “corrupt bargain,” with Clay delivering his voters in exchange for being appointed secretary of state.

Yet there’s no evidence that Clay did anything other than follow his conscience. Jackson would win the presidency four years later and be re-elected. Clay never reached the White House, despite two more chances in 1832 and 1844.

Clay, in defeat, acted as a check on what he saw as the autocratic impulses of the Jacksonians. “I have only two regrets,” Old Hickory said after leaving office. They were that he failed to “shoot Henry Clay” and that he “didn’t hang” the South Carolina secessionist, Senator Calhoun.

Clay, in his legislative career, shepherded the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 between North and South. The legislation delayed the Civil War, buying time for the Union to build the industrial might that proved decisive to its victory.

Although a slaveowner, Clay opposed the practice as a “great evil” and wrote the Washington, D.C., petition to ban the practice. In “Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union,” Robert Remini wrote that “it may have occurred to Clay that his apparent middle-of- the-road position invited attacks from both sides.”

Clay stood his ground, even though it hurt his chances of winning the presidency. He became known as “the Great Compromiser” and, when he died in 1852, America lost a voice for ending slavery without violence.

Today, Clay is remembered not as a three-time presidential loser but as a man who put the public’s best interests first. Mr. Mamdani’s opponents, as pressure grows to unify behind a single candidate, can ponder that legacy. Maybe one or more of them will decide that they’d rather be right than be mayor.