This Constitution Day, James Wilson’s Insistence That ‘We the People’ Are the Bedrock of ‘Lawful Government’ Resonates Anew

To Lincoln the fundamental principles of the Declaration are an ‘apple of gold’ framed by the Constitution, a ‘picture of silver.’

When it comes to celebrating Constitution Day, it may be considered atypical to think of the Declaration of Independence. After all, the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were two separate documents authored 11 years apart, written for two very distinct reasons, and penned by different authors.

Yet both documents were integral in creating the political philosophy of the United States of America. Both feature famous phrases that are studied and memorized by each rising generation of Americans in classrooms and on naturalization tests. Both documents have been invoked by politicians, activists, and leaders to strengthen arguments or to solidify a point.

Presidents, too, have used the Declaration and the Constitution in their speeches and writings. President Lincoln once described the fundamental principles of the Declaration as an “apple of gold” that was framed by the Constitution, a “picture of silver.”

Before Lincoln, however, no figure tied the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution more closely together than James Wilson, an immigrant with a Scottish upbringing and education. Wilson was quite familiar with the founding texts, as he was only one of six men to sign both documents.

A student of the Scottish Enlightenment, Wilson was committed to the idea that government existed to secure the natural rights of individuals. Two years before the Declaration of Independence, he published a pamphlet titled “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament.”

In it, Wilson denied the legislative authority of Parliament and laid out an important teaching on political theory that would be echoed by President Jefferson in the Declaration:

“All men, are by nature, equal and free: no one has a right to any authority over another without his consent: all lawful government is founded in the consent of those who are subject to it: such consent was given with a view to ensure and to increase the happiness of the governed, above what they would enjoy in an independent and unconnected state of nature. The consequence is that the happiness of the society is the first law of every government.”

Noted historian Carl Becker argued that Wilson’s pamphlet laid the foundation “for the general theory which Jefferson was later able to take for granted as the common sense of the matter.”

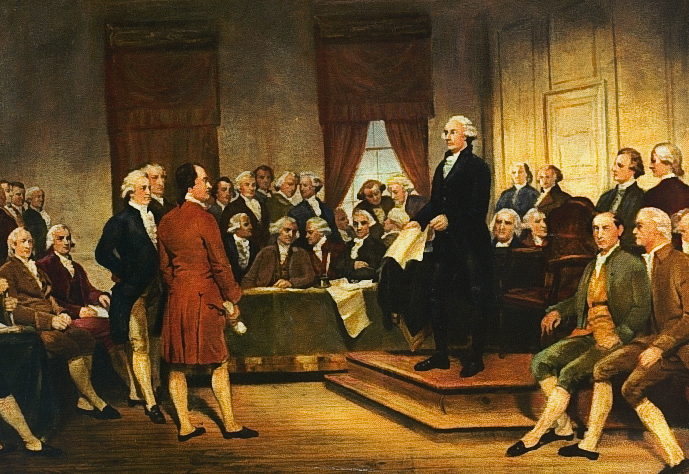

In 1787, as a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Wilson penned the first draft of the Constitution, including its famous opening “We the People.” More than any other delegate, he stressed the importance of citizens having a voice and representation in government.

Toward that end, Wilson used the Declaration for his constitutional arguments. In fact, he even commissioned a special copy of the Declaration to be made for the proceedings. On June 19, 1787, Wilson read the Declaration, “observing thereon that the United Colonies were declared to be free & independent States; and inferring that they were independent, not Individually but Unitedly and that they were confederated as they were independent, States.”

During the ratification debates in Pennsylvania, Wilson once again used the Declaration as a device to further his argument for ratification. In his speech on November 26, 1787, he claimed that the Constitution was the means to “the great end” the Founding Fathers hoped to accomplish. It was a constitution that would produce the advantages of good, and prevent the inconveniences of bad government — a constitution, whose beneficence and energy would pervade the whole union, and bind and embrace the interests of every part — a constitution that would ensure peace, freedom, and happiness, to the states and people of America.

On December 4, 1787, he quoted Jefferson’s famous second paragraph of the Declaration and announced, “This is the broad basis on which our independence was placed: on the same certain and solid foundation [the Constitution] is erected.”

The following July, the country celebrated its first Fourth of July under the new “supreme law of the land.” At Philadelphia, Wilson was the keynote speaker for the city’s celebration of independence. With over ten thousand people in attendance, Wilson could not help but tie the Constitution to the day’s festivities.

He closed his oration with a vision for the United States under its new Constitution: “Peace walks serene and unalarmed over all the unmolested regions — while liberty, virtue, and religion go hand in hand, harmoniously, protecting, enlivening, and exalting all! Happy country! May thy happiness be perpetual!”

As we celebrate Constitution Day amid a presidential election filled with heated rhetoric, Americans should reflect on the political philosophy that is the bedrock of our nation: That both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution ensure that “We the People” live out the true meaning of our creed that “all men are created equal.”

This article was originally published by RealClearHistory and made available via RealClearWire.