Three Hollywood Lives Led the Hard Way

Biographies of screenwriter Mary McCall, actress Joan Crawford, and singer Helen Morgan illustrate some of the struggles behind all of the glitz and glamor.

‘Mary C. McCall Jr.: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Most Powerful Screenwriter’

By J.E. Smyth

Columbia University Press, 312 Pages

‘Joan Crawford: A Woman’s Face’

By Scott Eyman

Simon & Schuster, 464 Pages

‘Helen Morgan: The Original Torch Singer and Ziegfeld’s Last Star’

By Christopher S. Connelly

University Press of Kentucky, 394 Pages

In 1950s Detroit, I grew up smitten with Ann Sothern in Maisie movies shown on Channel 9, CKLW (Windsor, Canada). I had no idea the films, depicting a beautiful, tough, feisty working girl, were written by Mary McCall. A novelist and Hollywood powerhouse, elected the first woman president of the Screenwriters Guild, McCall eventually fell afoul of Howard Hughes, in his heyday as RKO mogul, and of the blacklist.

During the 1940s and 1950s, when McCall reigned, Joan Crawford was having a career revival at Warner Brothers, beginning with her summa, “Mildred Pierce,” playing a hardworking woman — if no Maisie — setting herself up in the restaurant business, yet remaining always, in soft focus, the mature glamour queen. What McCall might have made of Crawford we will never know. She is not mentioned in Mr. Eyman’s biography.

Influential film scholar Jeanine Basinger deems Mr. Eyman’s biography faithful to the star and woman she knew: “her humor, her intelligence, her work ethic, her generosity, and her determination as well as her insecurity.” Crawford knew that what happened to McCall could happen to her — and in fact had happened to her when she was considered a has-been before her Warner Brothers rebirth.

Mr. Eyman reports that a Warner Brothers executive, Steve Trilling, told the director of “Goodbye, My Fancy,” Vincent Sherman, to avoid close-ups of his star because she was “getting too old.” Crawford was playing a congresswoman whose anti-fascism, anti-war film becomes a controversial issue for her former lover and college president, Robert Young, who has invited her back to her alma mater for an honorary degree. In true Hollywood fashion, the film skirts blacklisting and McCarthyism, seeking to offend no one while preserving their star’s luster.

Such films were produced at a time when McCall was fighting for a minimum wage and pay raises that to her champions made her an “avenging goddess” and to her detractors “the meanest bitch in town.” Crawford could be just as bitchy, so far as certain Hollywood insiders were concerned, but not on screen. Crawford worked every day, it seems, not to be forgotten or overlooked, but she would not be caught with a pipe in her mouth and a drink in her hand, as in the cover photograph of “The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Most Powerful Screenwriter.”

As Mr. Eyman deftly demonstrates, Joan Crawford knew how to survive in Hollywood as the daring product of a studio system she knew how to challenge — but only up to a point. Whatever trouble she caused studios, she was, in essence, a collaborator, and not nearly as conflicted in her attitude toward stardom as were some of her fellow stars.

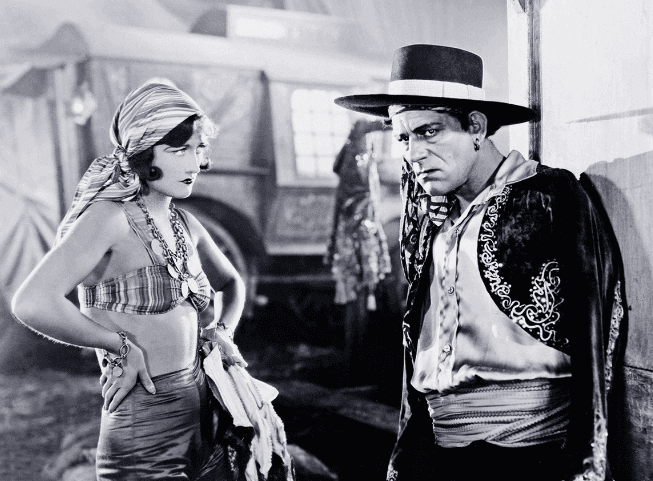

Helen Morgan sang dolefully, draped over a piano; she danced; she performed on Broadway, in film, and on radio; she excelled in comedy sketches, yet she could not control her alcoholism, or negotiate the perilous obstacles that a woman like Joan Crawford confronted and conquered. Like Crawford, Morgan got an early start in silent films, but was typed early on, and treated as though her life was a cabaret.

That spectacle of the nightclubbing, speakeasy-going Morgan stuck with her after her arrest on December 20, 1927, shortly after the opening of “Showboat,” in which she starred as Julie La Verne singing about the lazy, crazy man she loves. As Christopher Connelly observes, she could turn a torch song into a one-act play: “Audiences had never experienced anything like her.” Could she do more than that? It seemed to be the perennial question of her career.

Morgan could not re-invent herself as Joan Crawford did, transforming herself from dancer to dramatic actress, or even sustain a character through 10 movies as Ann Sothern did with Maisie. Neither Sothern nor Crawford, of course, wanted to take on the studios, to change the very conditions of their employment, which is exactly what McCall did, even to her own detriment.

Mr. Rollyson is author of biographies of Marilyn Monroe, Dana Andrews, Walter Brennan, and Ronald Colman, as well as a work in progress, “Our Eve Arden.”